Much has been written about the spectacular pan-India success of the recent Allu Arjun-starrer Pushpa that should be called a ‘Telugu film’, but is instead an ‘Indian film’, given its 5-language release strategy (Telugu, with dubbed versions in Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, and Hindi).

Baahubali, in a way, was the forerunner of this ‘invade and conquer North’ strategy, and a lot of films from the south have tried the same tactic since then, including Sudeep’s Pailwaan, Yash’s KGF (Kannada + other languages), Dulquer’s Kurup (Malayalam + other languages), Rajinikanth’s Annaatthe streamed on Netflix in multiple languages, and so on.

Now, Allu Arjun is among the many male actors (like Ram Pothineni, Ram Charan, Gopichand, and so on) who have pitched themselves into regions far beyond their home state. This seamless movement between states and languages in India was once the domain of leading ladies – it was very common for Southern leading ladies to act in Hindi and vice versa. In fact, many Tamil and Telugu films thrive almost exclusively on ‘North India’ leading ladies given the obsession with fair skin.

This trend was then open to villains, but rarely to leading men.

But now, much of this broader canvas for male stars was because of the dubbed versions of their films on satellite TV. This trend has been accentuated due to dubbed and subtitled films on OTT/streaming platforms now.

And given the pan-Indian popularity of films from Kerala, a true cultural revolution seems to be taking place in India. No, we are not going language-agnostic – far from it. The interest in Indian languages continues, but we seem to be open to an amalgamation of regional cultures more readily.

Case in point: the recent Malayalam film Bheemante Vazhi had a lead female character who was from Karnataka (clearly mentioned in the film) and spoke broken Malayalam. And another Malayalam film, Thinkalazhcha Nishchayam (insanely enjoyable!) had side characters who were Bengali. I’m sure there are a lot more examples of this cultural and linguistic mix-and-match, but this is a far cry from a lone Ek Duje Ke Liye in the 80s that dared to show a Tamil-speaking leading man in a Hindi film (and Kamal Hassan’s Hindi career was extremely short-lived).

But even as all this cultural amalgamation is gradually happening in the world of cinema, the advertising world still seems to be getting its language and cultural nuances awkwardly wrong.

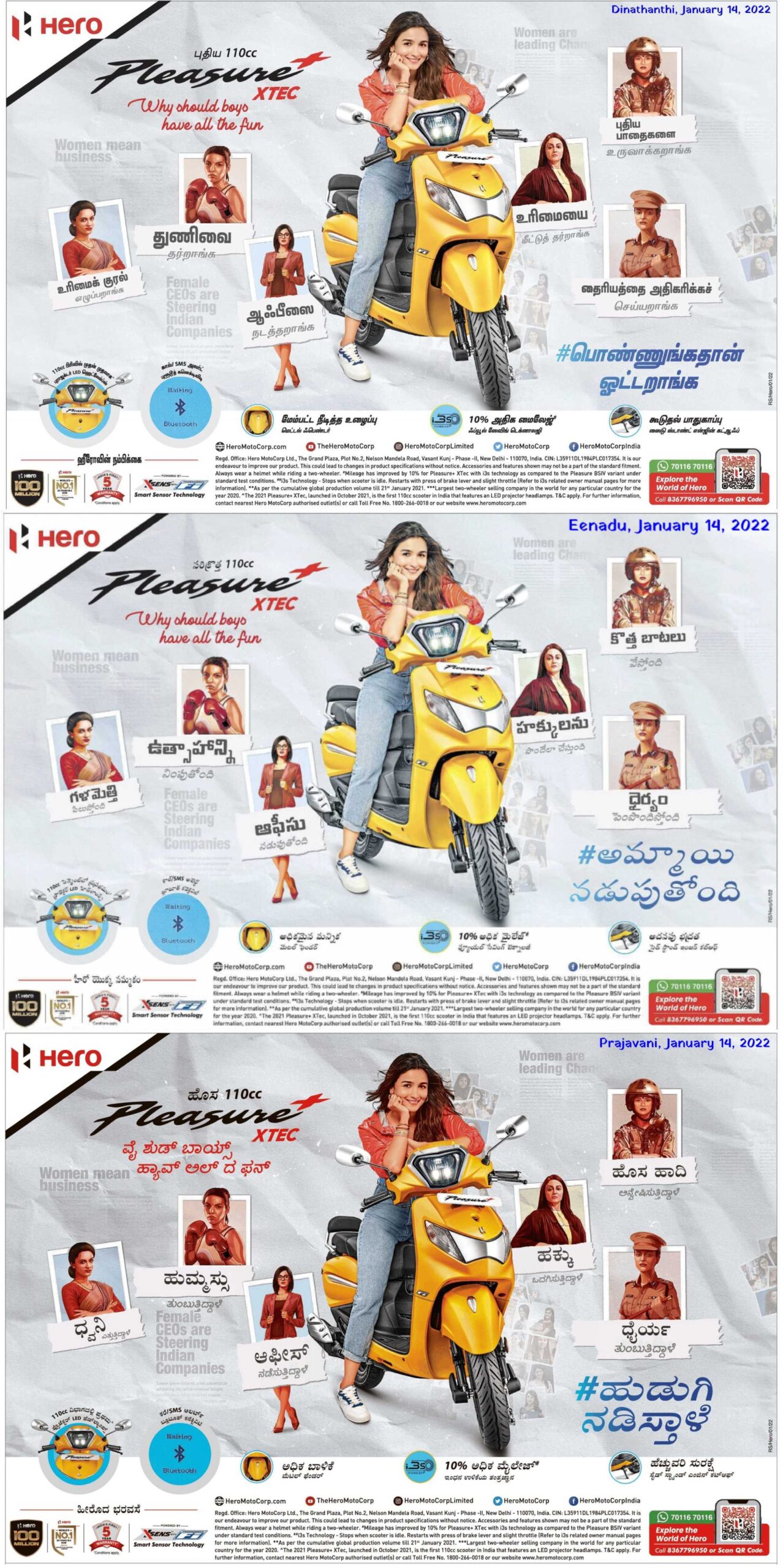

Consider this Hero Pleasure XTEC ad that was released in many newspapers across India on the same day recently.

The Hindi version of the ad, in Navbharat Times, is fully in Hindi, except the statutory copy at the bottom. The 7 women portraits are in Hindi and even the brand’s famous tagline, ‘Why should boys have all the fun?’ is written in Hindi script.

Compare that with the other Indian language versions in Dinathanthi (Tamil), Eenadu (Telugu), and Prajavani (Kannada). Almost fully in the respective regional languages, including the 7 women portraits. The Tamil version has the tagline in English, unlike the Telugu or Kannada version that mirrors the Hindi approach of writing the English tagline as is in Kannada and Telugu script.

So far, so good. Why? Because the Hindi ad was published in a Hindi language newspaper and the Tamil, Telugu & Kannada ads were published in Tamil, Telugu & Kannada language newspapers, respectively – and as per conventional advertising norm, the brand and agency have stuck to the respective languages as per the release medium.

By this logic, what should the ad look like in an English language newspaper printed for the Chennai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, and Kochi editions?

a. Should it be in Tamil, Kannada, Telugu & Malayalam, but written in English script?

b. Should it be in English itself, all through, considering the language of the newspaper is English?

Observe what the brand and its agency eventually ended up doing.

Most brands and agencies still think on the lines of ‘one hero film in Hindi + regional versions’ primarily because Hindi will, in most cases, be understood by most people in India after decades of multiple Central Governments pushing it pan-India, in terms of education, incessantly. So, understanding Hindi, to some extent, is like understanding English, in India – as long as the words used are simple and often used, the basic message is likely to be understood most across India.

Even in terms of situations that the advertising world tries to script for their storytelling, they try to use universal emotional buttons that can transcend regional boundaries. When dubbed in assorted Indian languages, the required ‘feeling’ is conveyed adequately, then.

A shortcut to localization is to use regional celebs to replace national celebs. So, an Alia Bhatt for ‘North’ and Allu Arjun for ‘South’, as Frooti did some time ago.

Or, Tiger Shroff for ‘North’, and Mahesh Babu for ‘South’.

But I also see a silver lining in terms of cultural amalgamation in digital ads (may not be so much for made-for-TV ads).

Consider this hugely viral ad by Jar app that mercilessly mocks NFTs. It is shot in Bengaluru (obviously – at The Biere Club). But the lead guy, who had spoken in Hindi too earlier in the ad, blurts out an instinctively shocked ‘Ippattu laksha?’ (Twenty Lakhs in Kannada) completely naturally and out of the blue! 🙂

There was no need for this Kannada addition in the ad that is otherwise in a combination of Hindi and English. But that Kannada phrase increases the language quotient of this ad from two, to three, while also making it instantly more appealing to one state in particular.

Or take this new Olay India ad that localizes the brand’s global focus on STEM education for women.

It’s a truly pan-India ad with multiple regions represented and includes, besides English and Hindi, dialogs in Bengali and Malayalam too!

These are not ‘dubbed’ contraptions. These are ads where the creative teams are consciously thinking of either infusing the ‘local’ seamlessly or intentionally writing the scripts to appeal to ‘India’ and not merely targeted regions (which mandate more ‘local cuts’).

A Malayalam film like Bheemante Vazhi need not have a Kannada-speaking leading lady at all, but that addition adds a special texture to the film’s narrative. Jar need not have added that Kannada phrase at all in the ad, but that small addition suddenly makes the ad uniquely different.

But the difference between movies and advertising also plays a role in such nuances: with movies, the consumption of the content is the goal, while in advertising the consumption of the content is only the start. Once the audience consumes the content in advertising, it is supposed to persuade them to perform an action (call-to-action, as it is called in advertising) – to remember the brand being advertised in a positive light, or to consider buying it. To get people to do that, ads cannot merely entertain, they also need to infuse persuasion triggers appropriate to the brand/product/service category beyond simply engaging an audience. So they need to work harder than movies where the objective is to get people to watch.

Then it is all the more important to add regional/local nuances in advertising narratives because they appeal to specific audience sets and hence increase the efficacy of the triggers to action. But because there are early signs of broader acceptance of regional cultures in the national consciousness due to the way cinema is heralding it, advertising could do well to seek inspiration to go beyond ‘Hindi ad; regional dubs/cuts’ template and think broader.