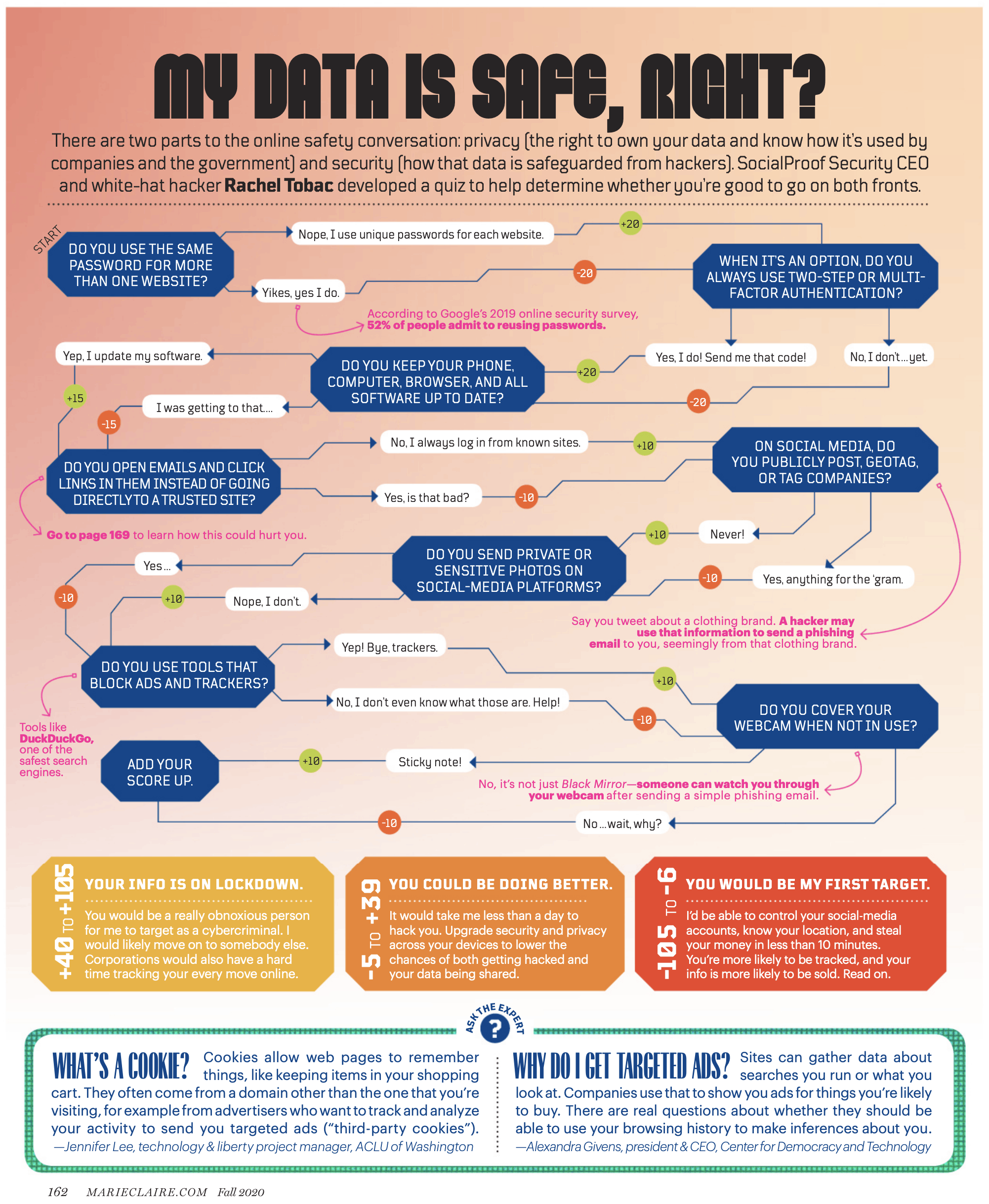

Back in October 2020, I noticed an online quiz in Marie Claire’s Fall 2020 issue created by a whitehat hacker, Rachel Tobac.

Here’s the quiz – try your luck.

Rachel had also tweeted about taking such quizzes for many other frivolous themes in the magazine, and that she was glad that she was able to produce a meaningful quiz like this one, on understanding the steps to protect your security and privacy online.

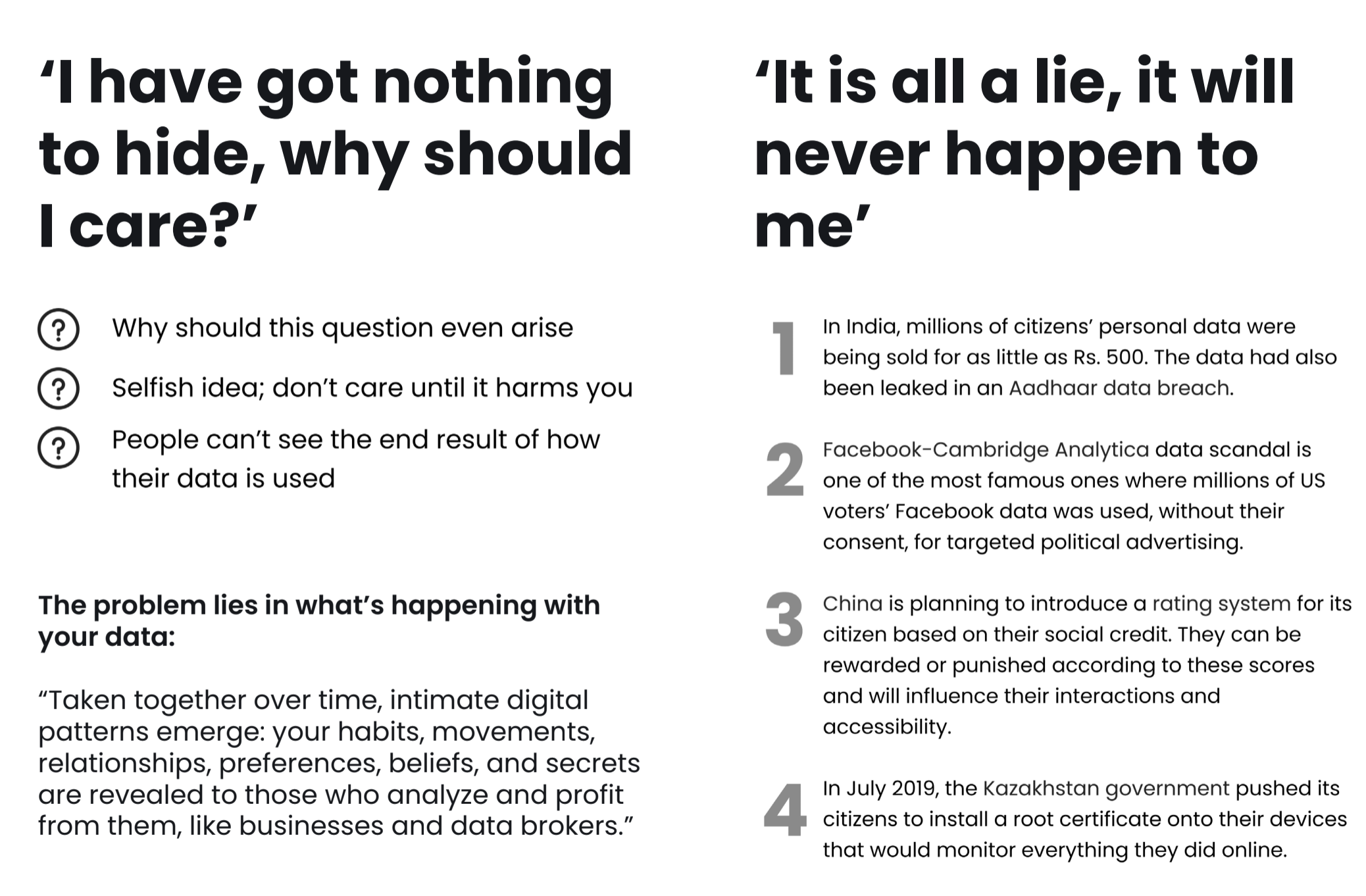

Given how complex the topic of online privacy and security is, and how people usually go, “If I have nothing to hide, why should I bother?”, I was pleasantly surprised to see another gamified effort to explain the same topic, but this time, from India!

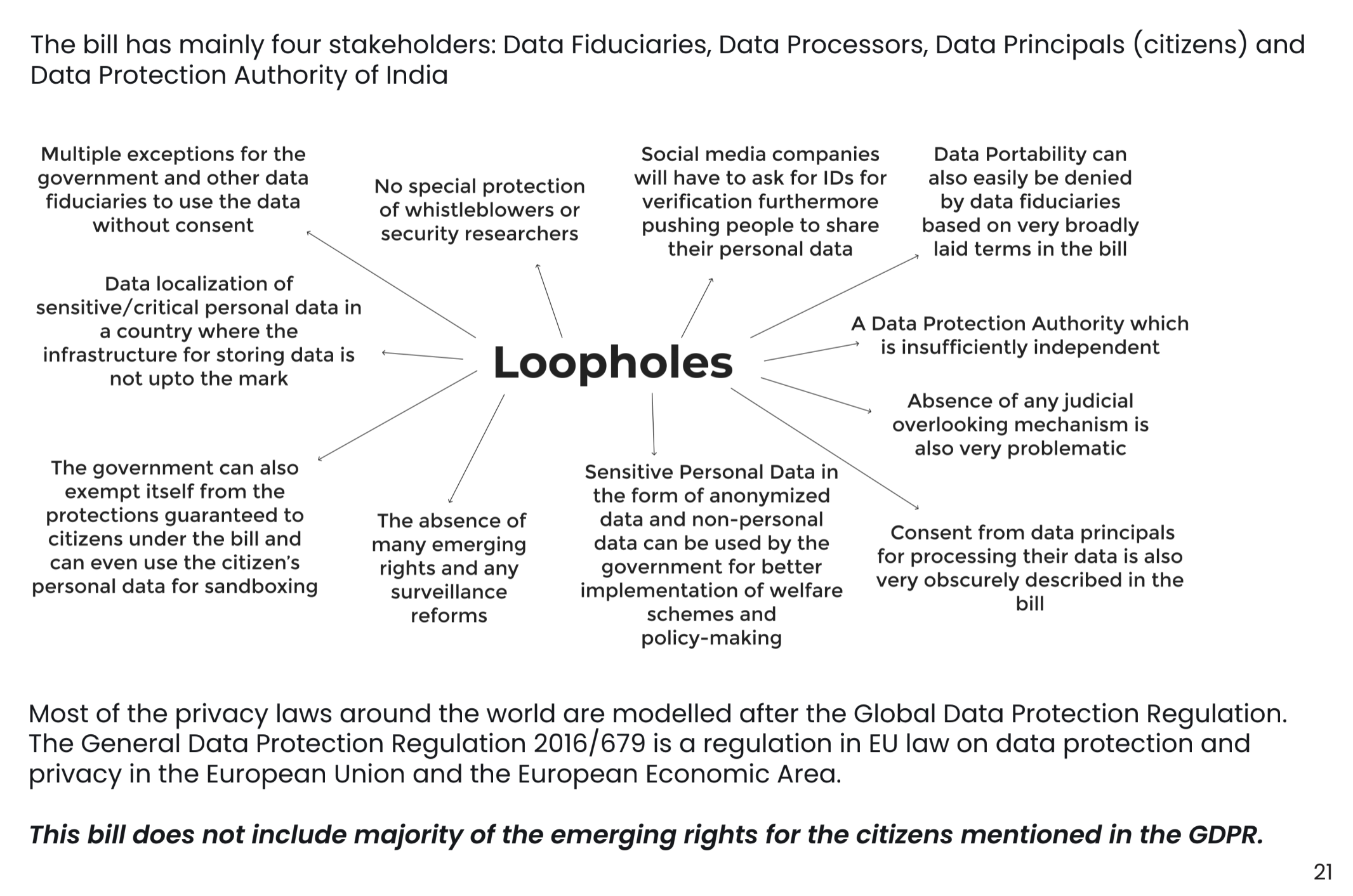

Ishita Begani, a UX Designer, has produced a card game to explain the complex nuances of India’s data protection bill and creating awareness about data privacy and data protection in general.

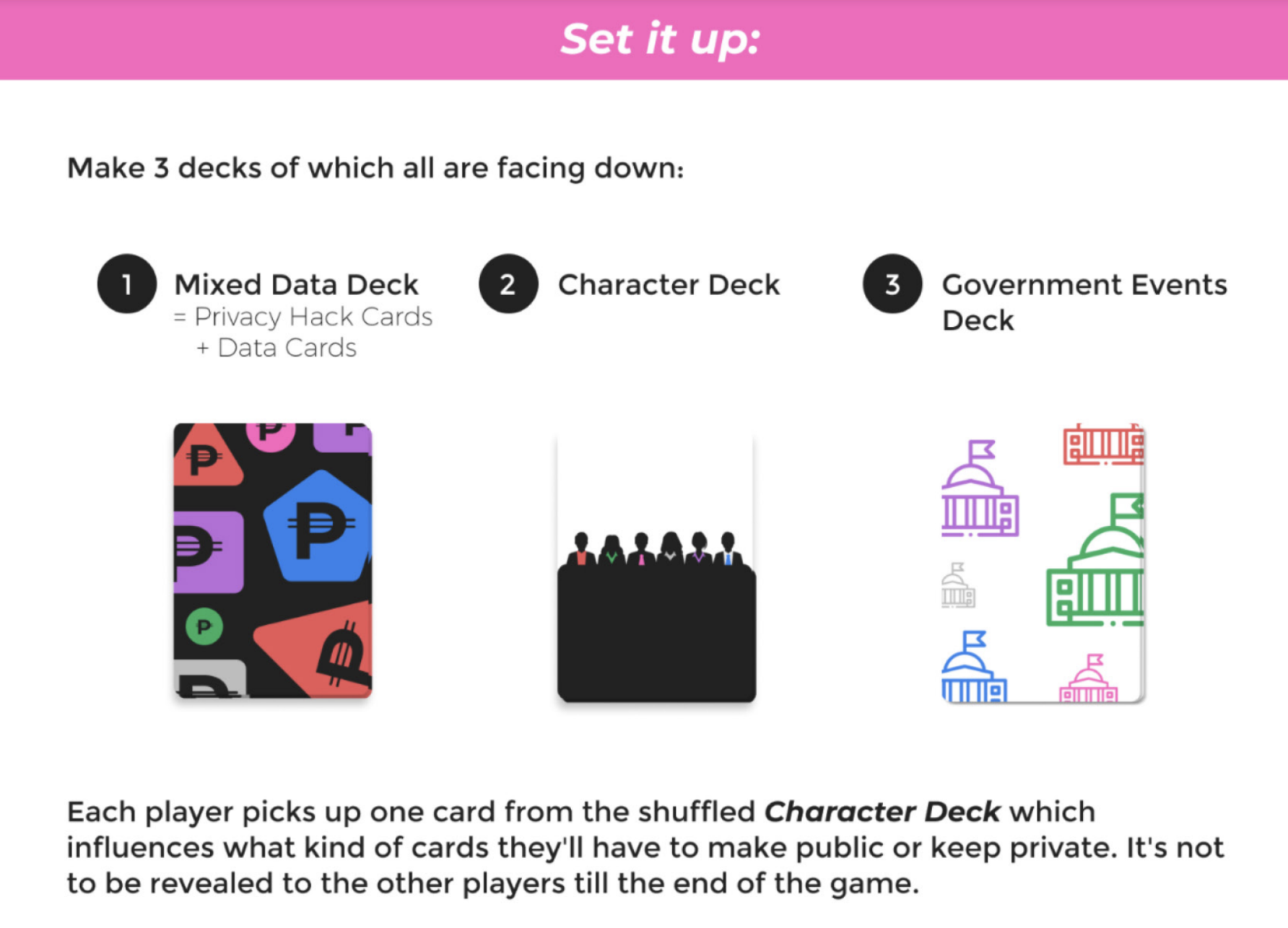

Given how incredibly complex these topics are, Ishita has done a phenomenal amount of groundwork to consider the details that are needed to even start building a game.

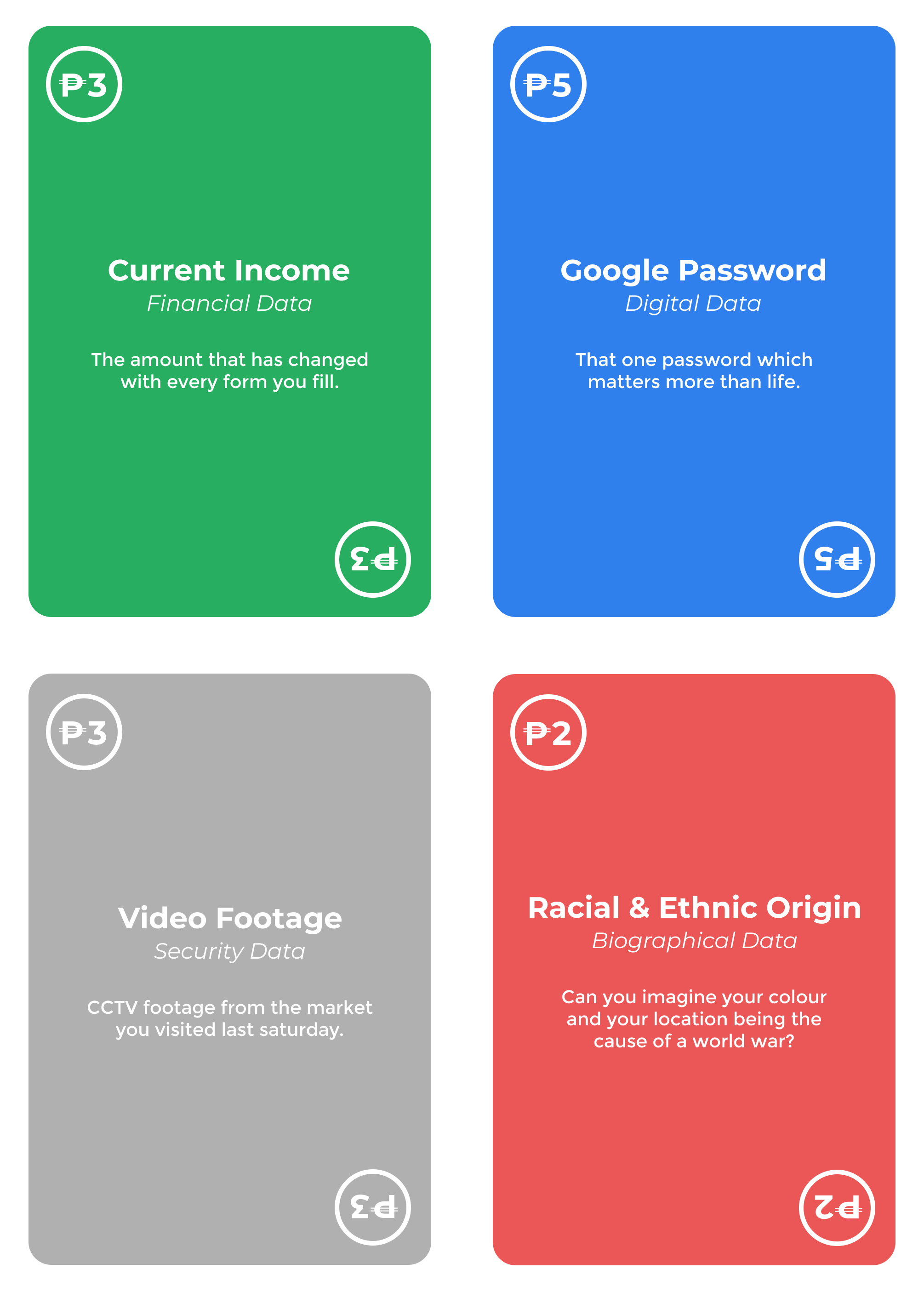

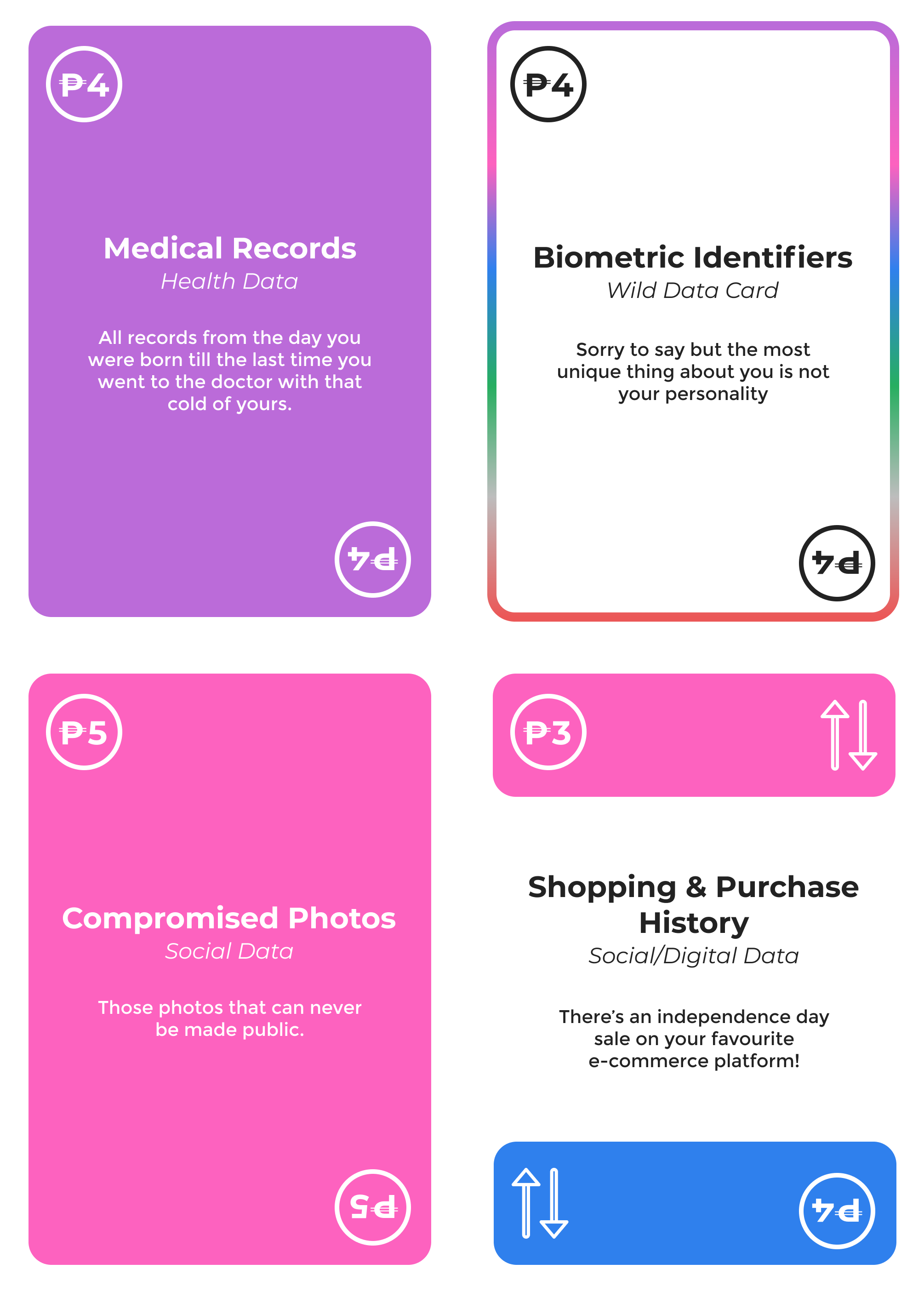

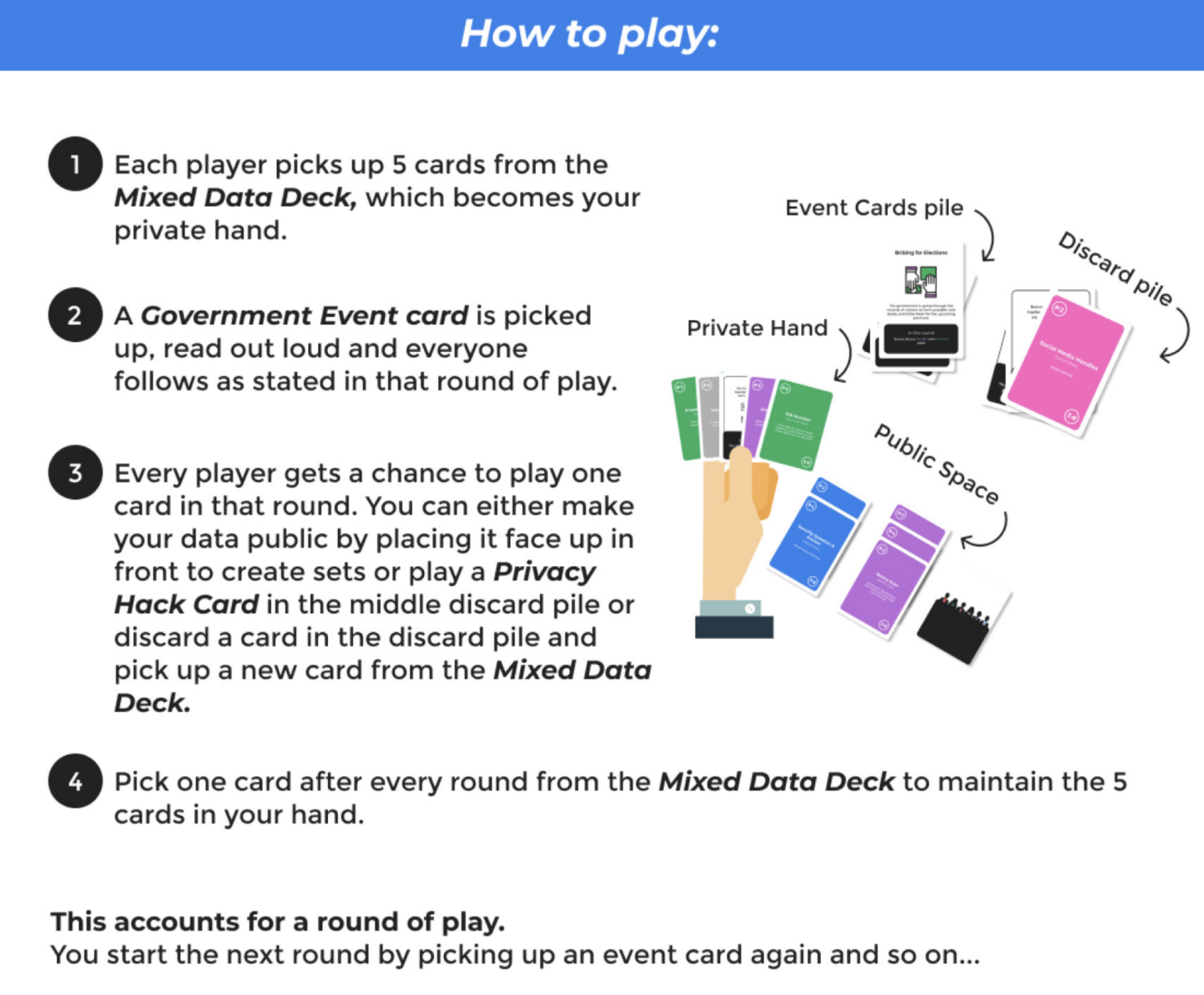

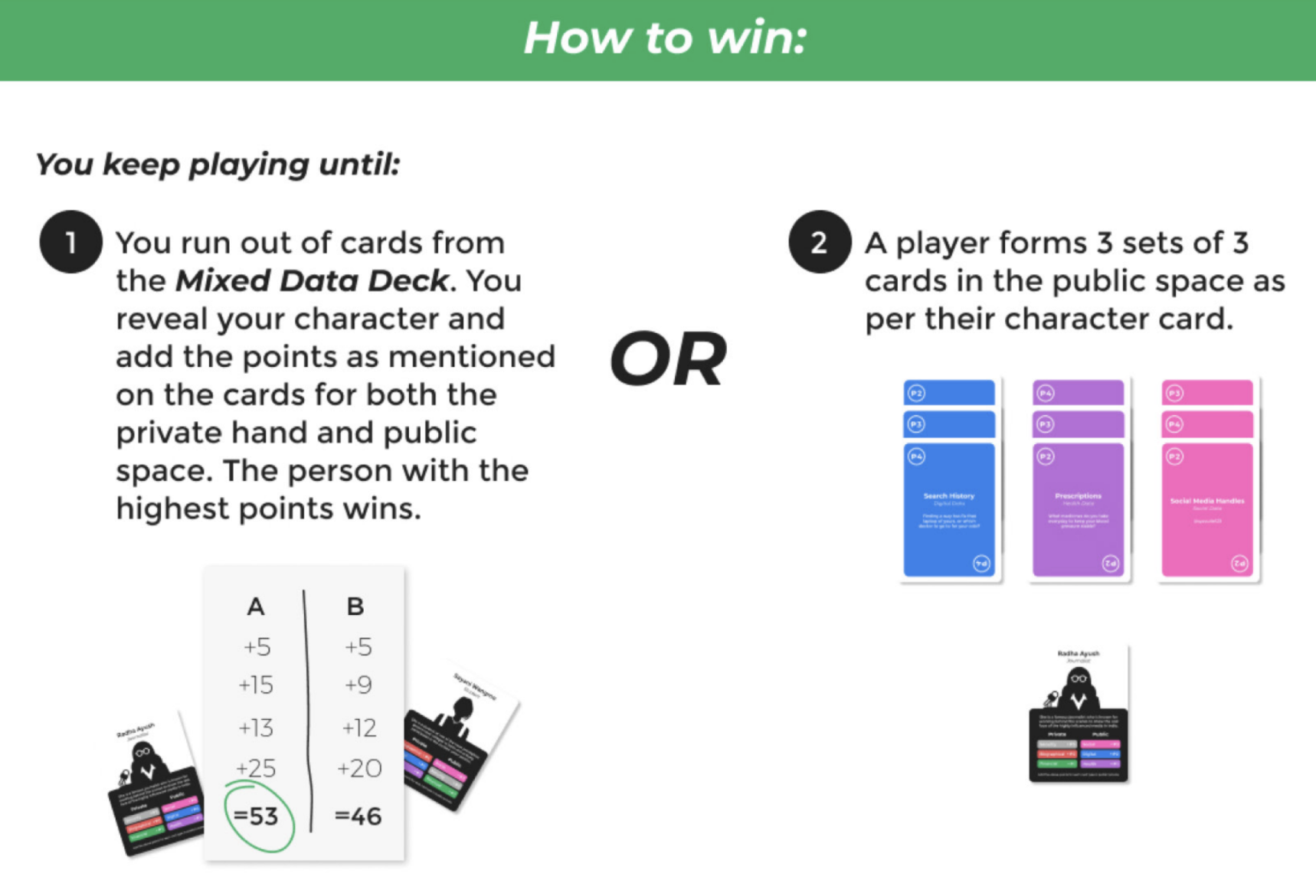

Ishita’s research (done as part of her undergraduate thesis) explains the thought process of how she ended up designing the game in excruciating detail. All that exploration of the topic shows up wonderfully when you see the final iteration of the game – a 112-cards pack with which you can play a card game like Uno or Cards Against Humanity (a party game).

According to the article published in The Hindu MetroPlus on February 23rd, Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), the Delhi-based digital liberties organisation, holds the licence to produce Ishita’s card game.

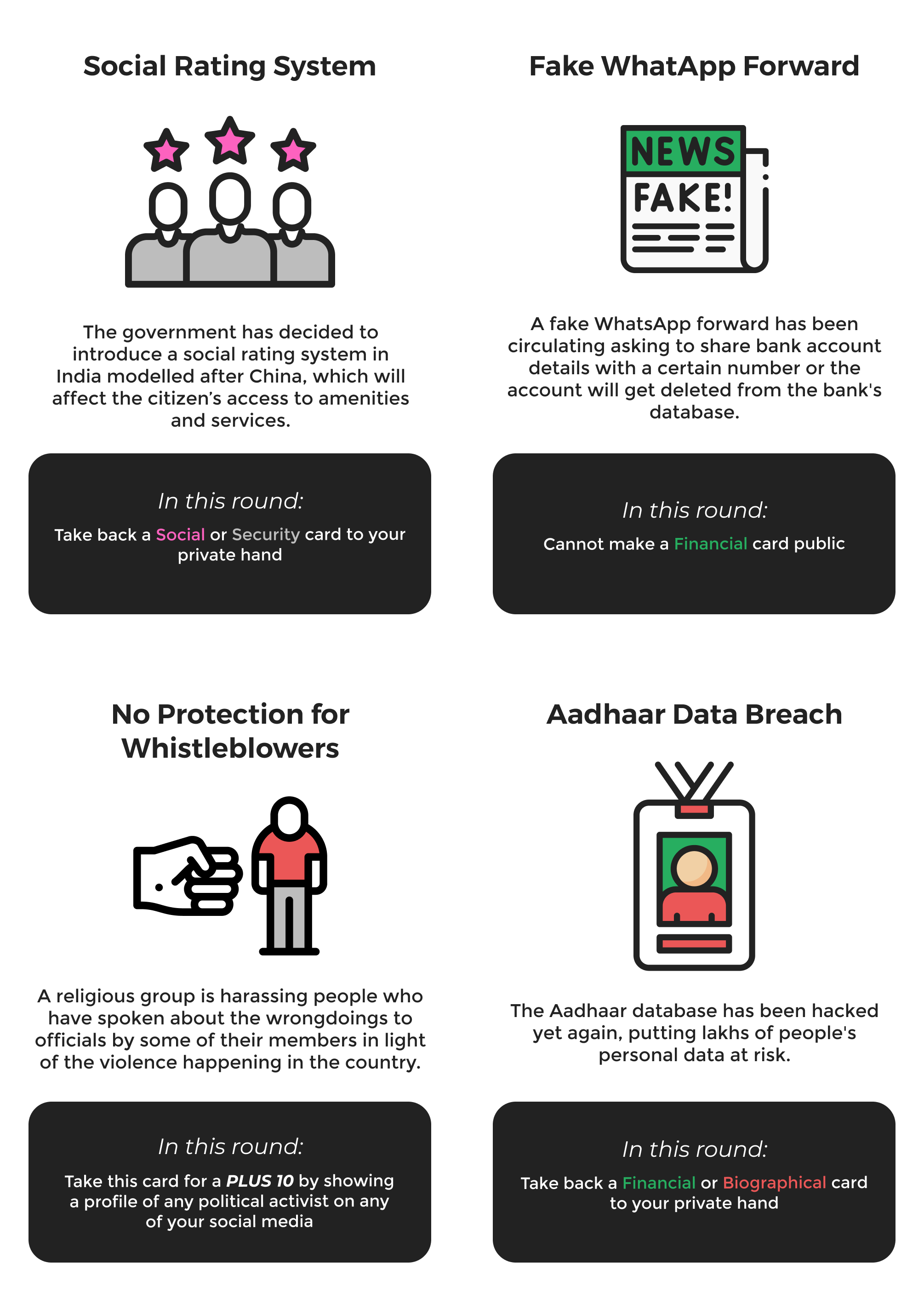

The game seems to be aimed at making people aware and evoke conversations around data privacy, data protection and worst-case scenarios when state (Government) and non-state players abuse or misuse your (citizens’) data.

This is not a mass-consumption game that can explain the data privacy bills nuances and pitfalls, and the basics around privacy online to a broad set of Indians. This seems more intended towards educating the educated (urban Indians) since even they are either uninterested in grasping the nuances of how many of the provisions in the data protection bill will affect them (despite a Joint Parliamentary Committee raising several concerns in the bill, including the kind of sweeping powers the Government gives itself over the data of Indian citizens) and how they can think harder in the event an adverse privacy event were to occur to them.

The card game is also a broad statement against powerful entities, both Government and private companies, that can use citizens’ data in hugely impactful ways, both positive and negative. And hence, this is clearly not for those who place their sweeping trust on entities, with assumptions like “the Government will ALWAYS do good to the people” or “large internet companies can’t harm me“.

I really loved the game’s design – it seems very detailed, precise and thought-through, keeping individual citizens in the mind, and imagined from their perspective, to create awareness and make every player question assumptions and prejudices around data privacy that come from our ignorance of the topic.

The use of gamification is so very apt for this topic since it involves so many permutations that make it difficult to grasp. An interactive game like this helps citizens question every aspect of their own decisions and the Government’s decisions, besides the decisions made on their behalf by internet giants, and act accordingly. Or, even if they cannot act in any decisive way, they could at least be aware (and prepared) of what they are doing and how it may affect them, now or in the future.

This is game design not merely intended to entertain or engage but to communicate something tangible. The game informs as much as it engages – the communication is the Trojan Horse aspect of this game.