Back in March this year, I had written about a 2016 ad film that spoke about organ donation in the most unusual way.

Here is that post/video, for context:

Let me continue that theme in this post, using 2 ad films made by Fortis Healthcare in India.

Their 2017 film was directed by Puneet Prakash, for the production house Color Features of India.

Watch the film:

The narrative in this film is highly emotional and uses a clever device in the script of making us think in a different direction about the conversation between the older couple (that is if you did not know the context of the film; but now that I’m sharing it under a post on organ donation, sorry to spoil that part. Please try to imagine the conversation without the awareness of organ donation theme to appreciate that script device).

My takeaway from this film was around acceptance. Organ donation is a very tricky subject in many cultures and religions. For various reasons (including fear of mutilation of the body – this is a myth), many people do not accept to donate the organs of their loved ones (after they are dead). Organ donation is also a family decision and this acceptance to let go, and accept another person as a carrier of a loved one’s organ is essential in convincing families to generously volunteer to donate, and save lives.

The actors in the film truly bring the film to life (pun absolutely not intended at all). Shernaz Patel is truly astounding with the look she gives her husband when he speaks in a loaded dialog at 01:05 – he tells her when she is protesting the very decision of her son’s choice of organ donation as not being done with her consent, that her son(‘s heart) will feel bad (sounds a lot more natural in the Hindi phrase, “bete ka dil dukhega”) if she doesn’t meet with the person who has the son’s heart.

There is a beautiful payoff in the end, for this line that evokes the son’s heart. I will not spoil this one for you – do take a look at it yourself. It’s a simple device (literally, and narrative as well), but one that is so wonderfully relevant to the film’s context of softening the stand of the mother.

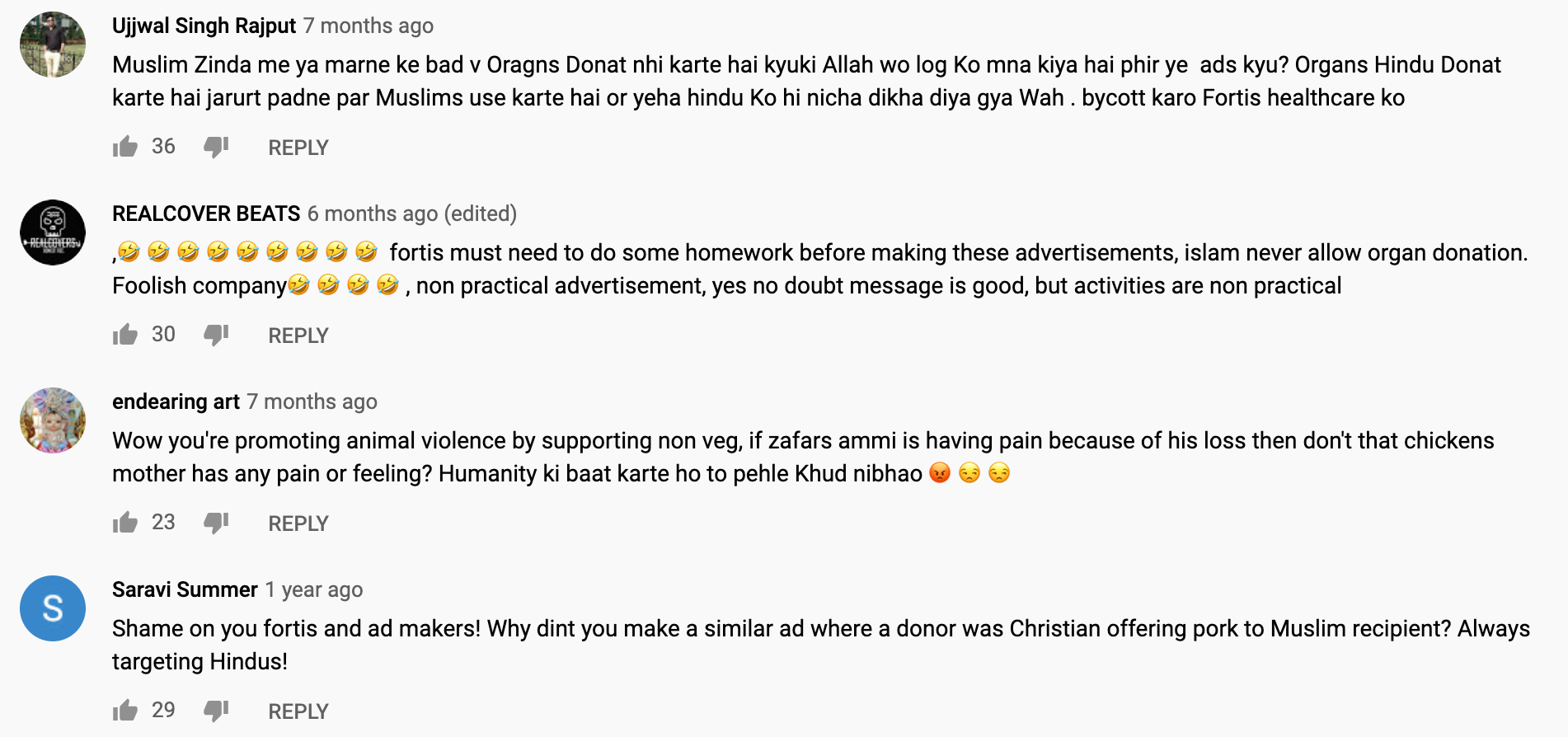

The 2018 film was also directed by Puneet Prakash, though this was conceptualized by Leo Burnett India.

Watch the film:

The connecting thread between the 2017 film and this one is ‘acceptance’, again. Both films look at the donor’s family accepting the new life of the organ of a loved one – in the earlier film, the mother had to overcome grief and accept the fact. In this film, the parents of the donor overcome their presumptions and accept that the recipient of their son’s organ is a very different person, with the same organ, however.

The donor’s family is shown to us as obviously Muslim, but the recipient’s family’s religious identity is not clearly denoted. Observe the wife not wearing a bindi, for instance. There are no markers to conclude that they belong to a particular religion. And this is important for the payoff in the end.

In the 2017 film, the conflict was the mother’s anger for her consent not being taken. In this film, the conflict is something more direct and visible – the non-vegetarian food that is served by the donor’s family to the younger couple. This is where the religion angle being left intentionally vague plays up in the comments section where many people commenting there assume that the younger couple is purely vegetarian and Hindu, and that they are forced to be magnanimous (and the connected trope – “Why is it that Hindus are always forced to be magnanimous?” as if magnanimity is bad behavior). The younger couple could also be vegans by choice or have shunned eating meat by choice – which seems perfectly plausible too.

From the perspective of the older couple, they made what they would have made for their own son, on their holy, festive occasion (Eid). And they are shown to be magnanimous too – the older man tells them that it’s not a problem (visibly embarrassed about his sweeping assumption, even though statistically, he is right in that assumption given that a majority in India are non-vegetarians). And the younger man volunteers to make the older couple happy by making an exception.

This is where there is a categorical direction of the younger couple having chosen to not eat meat, unlike not eating meat by birth. For people who have not eaten any kind of meat since birth because that’s how they have been brought up (I’m one of them), it is impossible to even consider eating it given the mental conditioning that has happened already. For him to even volunteer indicates that he has perhaps eaten it earlier and switched to not eating it by choice, for some specific reason.

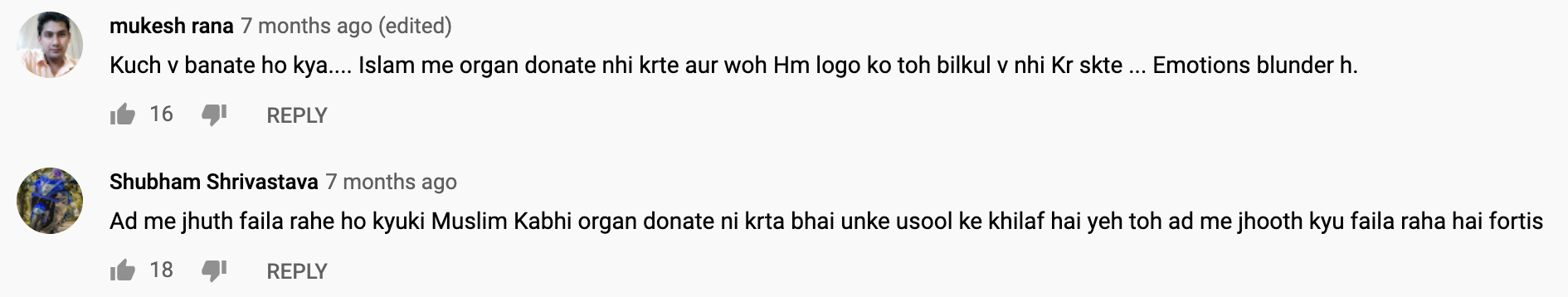

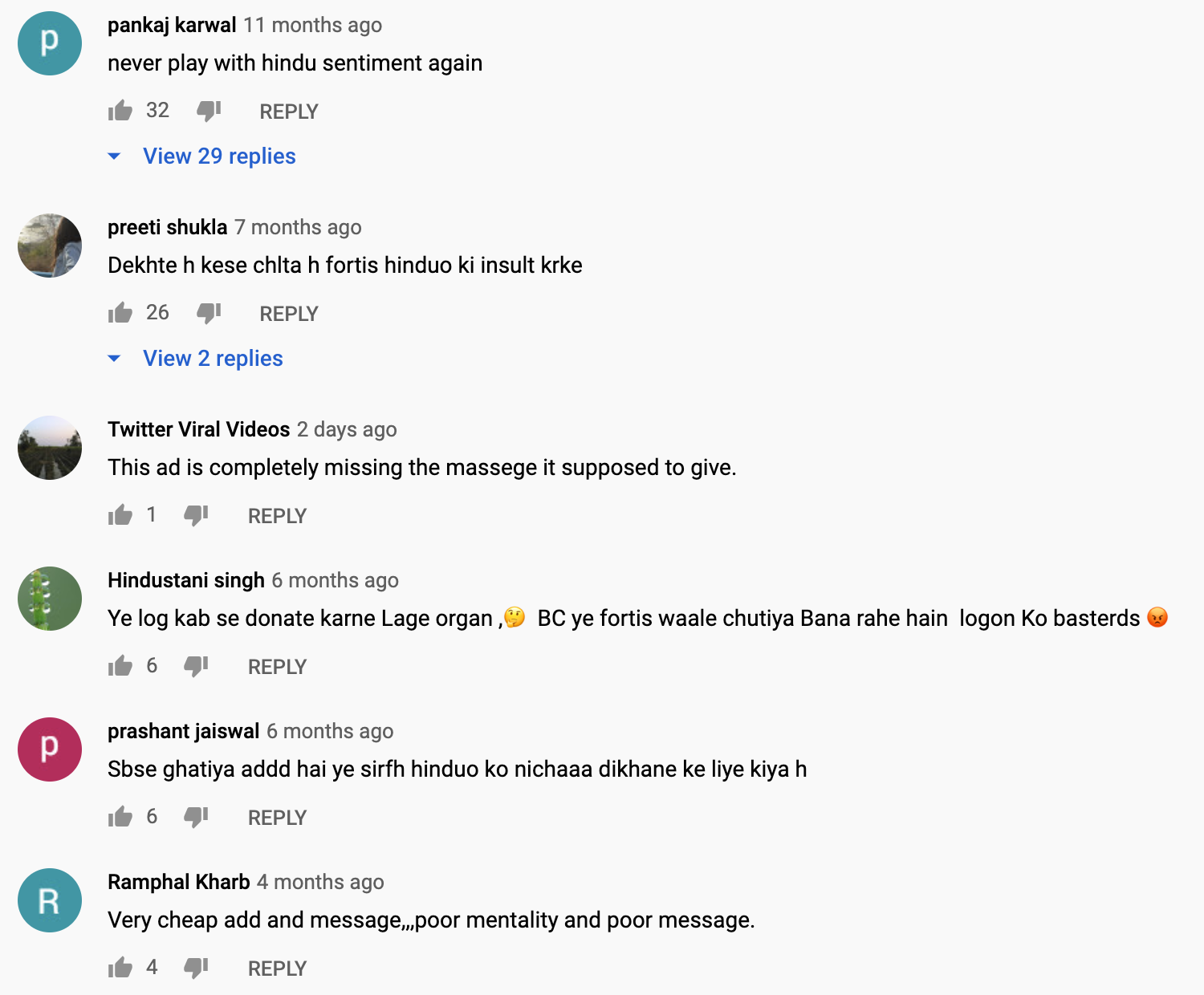

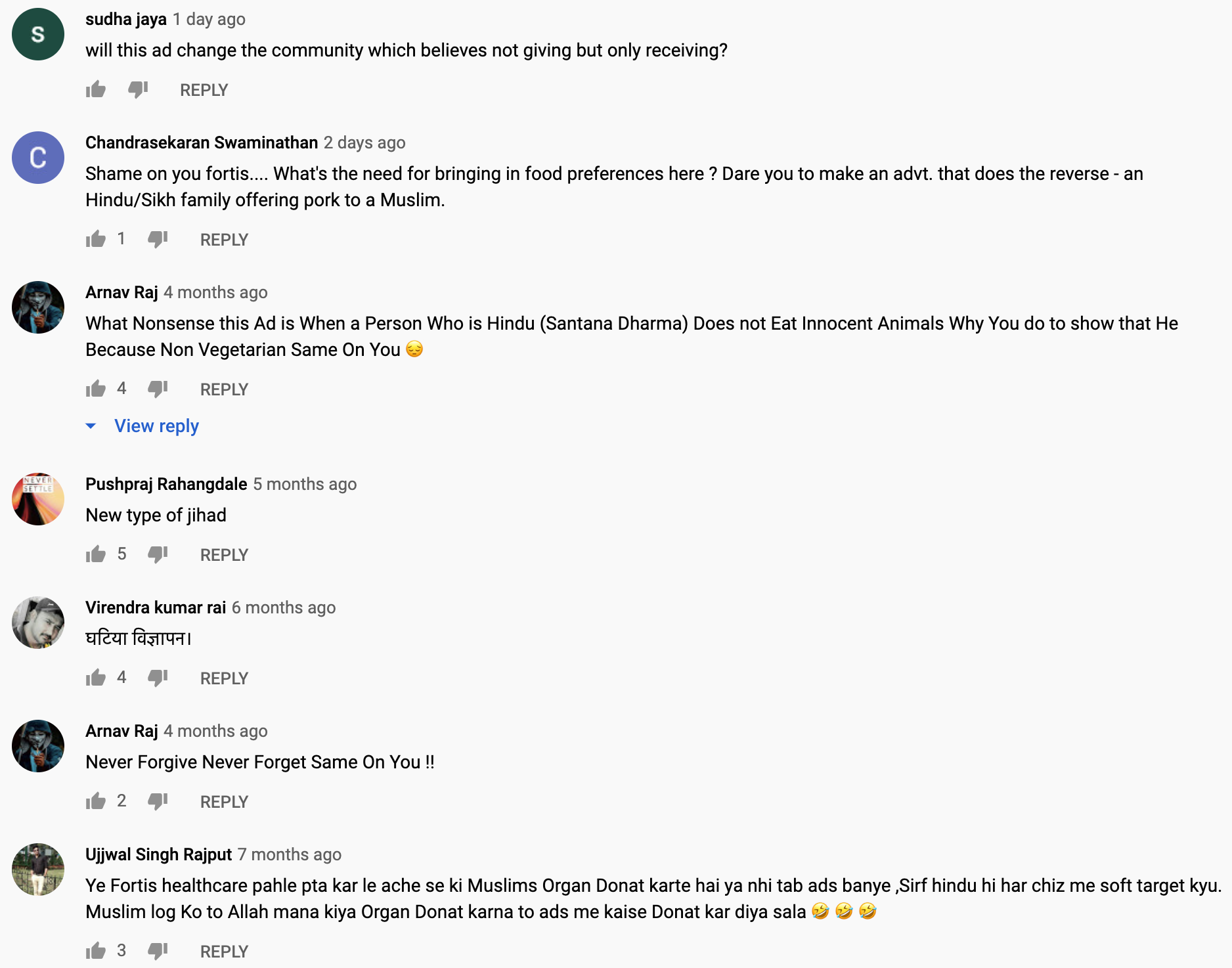

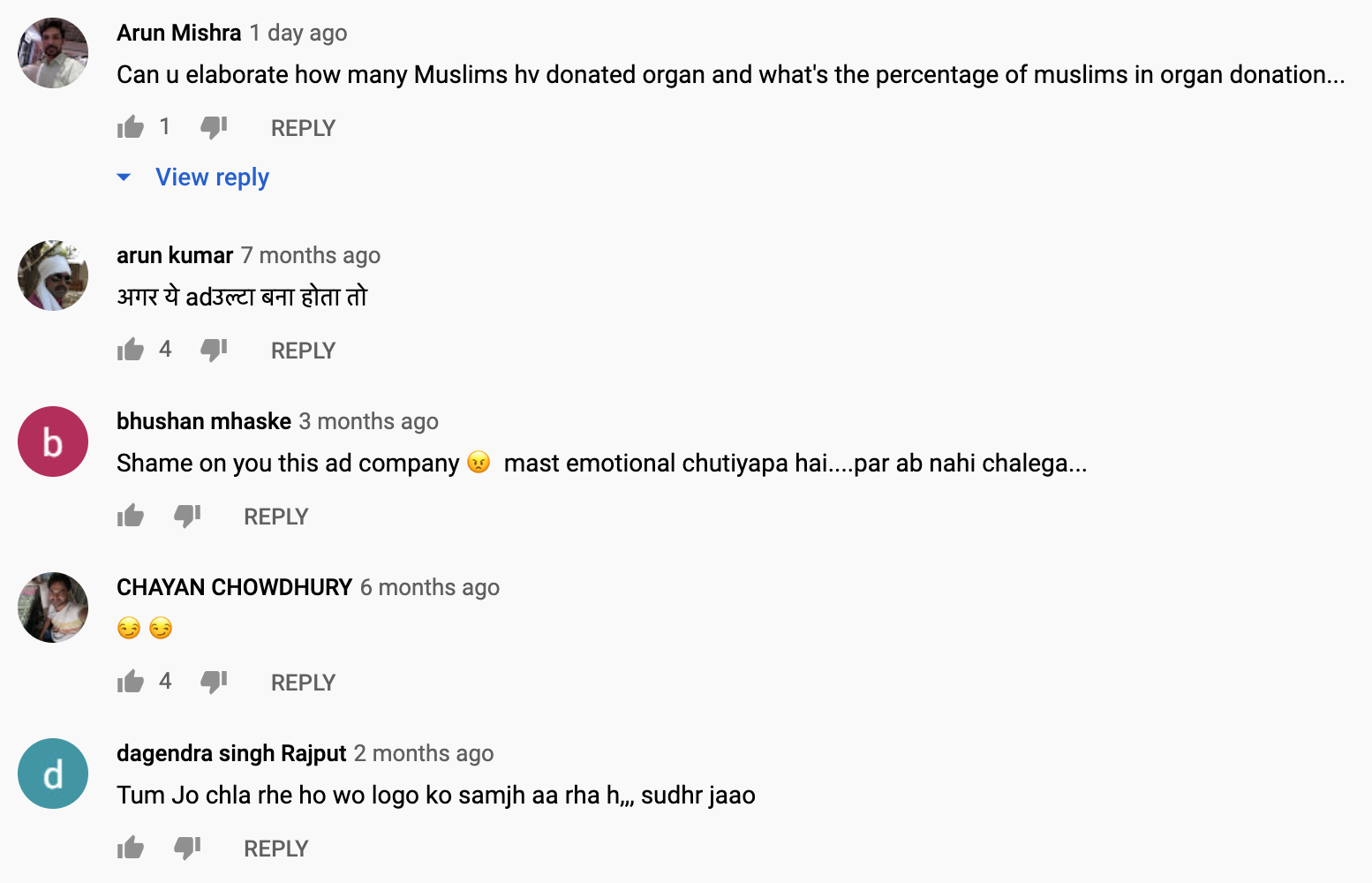

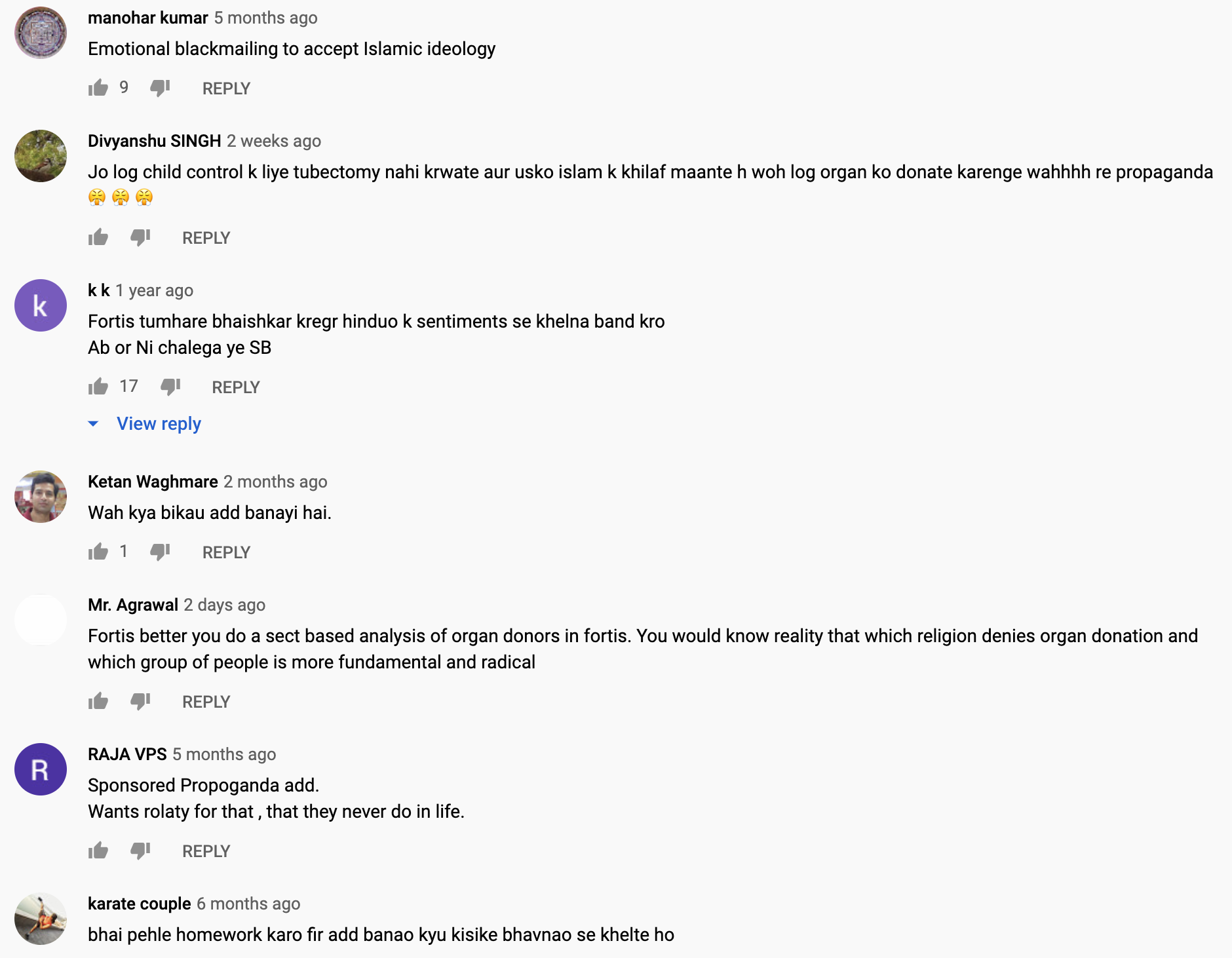

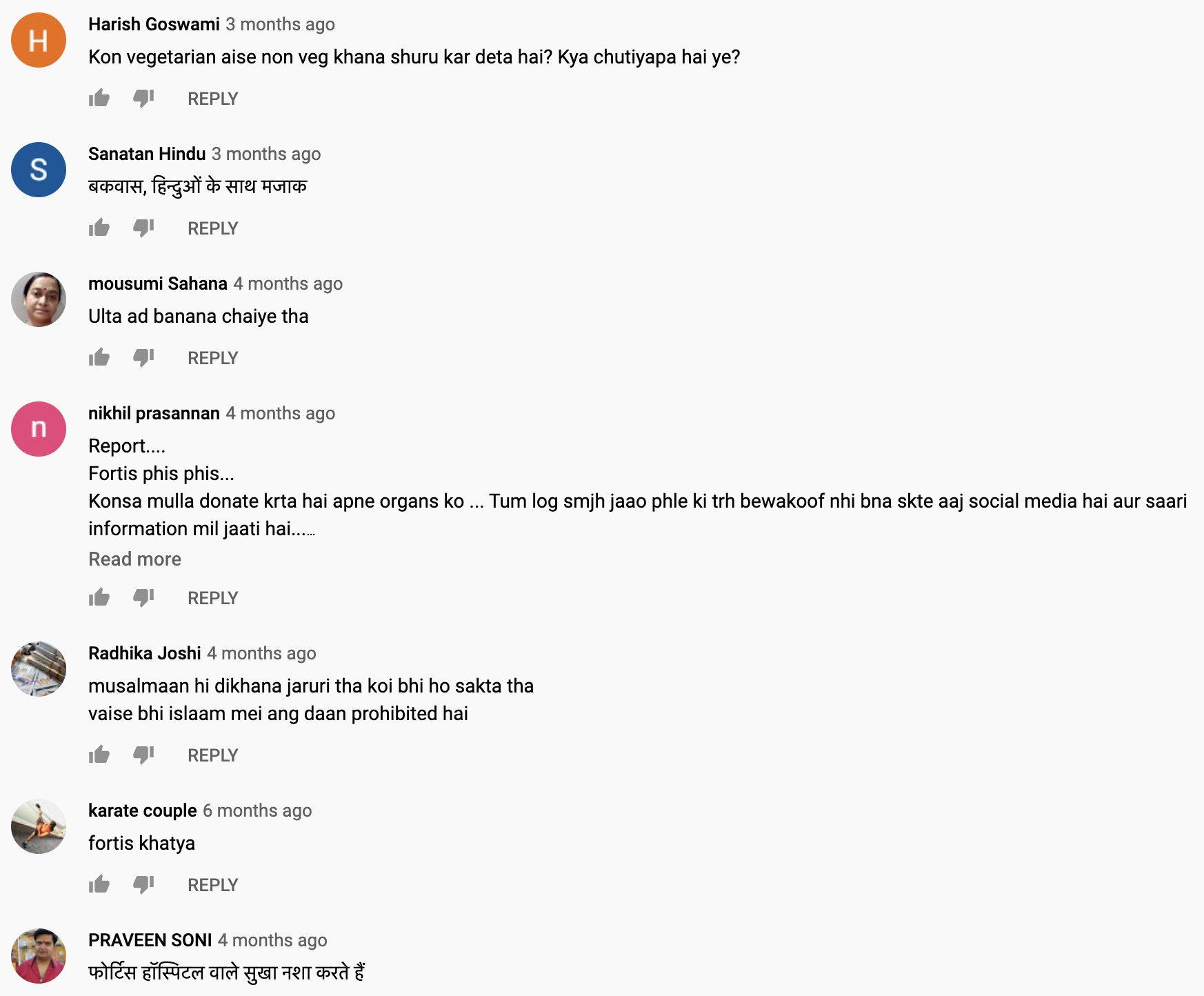

But, if you look at the comments on YouTube, you may replay the comments that landed for the now.

The 2 major threads in the comments are,

- Islam does not allow organ donation, so this ad is nonsense.

- Why should the ‘Hindu’ people go out of their way to please the older couple?

In both counter-points, there are serious flaws.

Islam may well bar organ donation as per the scriptures, and that is one of the points the ad intends to make – look beyond the religion towards the human angle. Do what you think is right in the interest of humanity, and keep your personal religious choices to yourself.

The 2nd point is a misdirection, of course, as I have explained it earlier.

There is also the suggestion that the film should have swapped the religions (even though the younger couple’s religion is not clearly indicated at all, unlike the Tanishq ad) – a young Muslim couple visit the Hindu donor’s family, and that the Hindu family should serve them pork. The question is, why would any decent, well-meaning and considerate Hindu family serve pork to someone who is obviously Muslim? Why would anyone want to be knowingly vile? And why suggest that the ad show Hindus as being intentionally mean?

If you go through the YouTube comments and the tone in which they are offered, you may have thought how this film escaped the kind of anger the Tanishq film evoked – the reactions are quite similar. So, for any ad that

dares to use the Hindu-Muslim angle in their narrative, it only takes one influential voice to spread negativity first as a sort of beacon to kickstart the outrage bandwagon. This film, thankfully, escaped that and I’m glad that it did, given how crucially important a message it is trying to communicate for the sake of saving lives, literally.

Both films make for a great watch.

The one problem in both the scripts is that, usually, the identity of the donor is not shared with the recipients. This is an angle I explored last week on an .

But, as I had mentioned in that post, I believe that narrative exaggeration (often explored in cinema) is reasonable enough if you consider the cause for which it is being applied.

Having made you read all this, it is only fair to request you to consider pledging your organs for donation. Here are 3 helpful links:

1

2

3

Incidentally, MTV India too is promoting the cause of organ donation with a quirky ad film!