One of the things you may notice in most smaller Indian restaurants is how they optimize the handwash experience to manage costs better. At the washbasin, there is usually a handwash dispenser, and this tends to be a Dettol or Lifebuoy dispenser, or a generic, unbranded one. But even if you see a branded dispenser, you could be sure that what’s inside is hardly branded. Because what you get when you press the dispenser is a liquidy soap instead of the thick soap that you may have expected upon seeing the branded pump.

Still, this is better than the one I first noticed, to my amusement, at the Manipal Hospital canteen on Old Airport Road in Bengaluru way back in the year 2000 when I first landed here for only my 3rd job: they had a bowl of liquidy soap water with a spoon! 🙂

This is only about soap, but what Heinz does in its new campaign is about something we consume – ketchup!

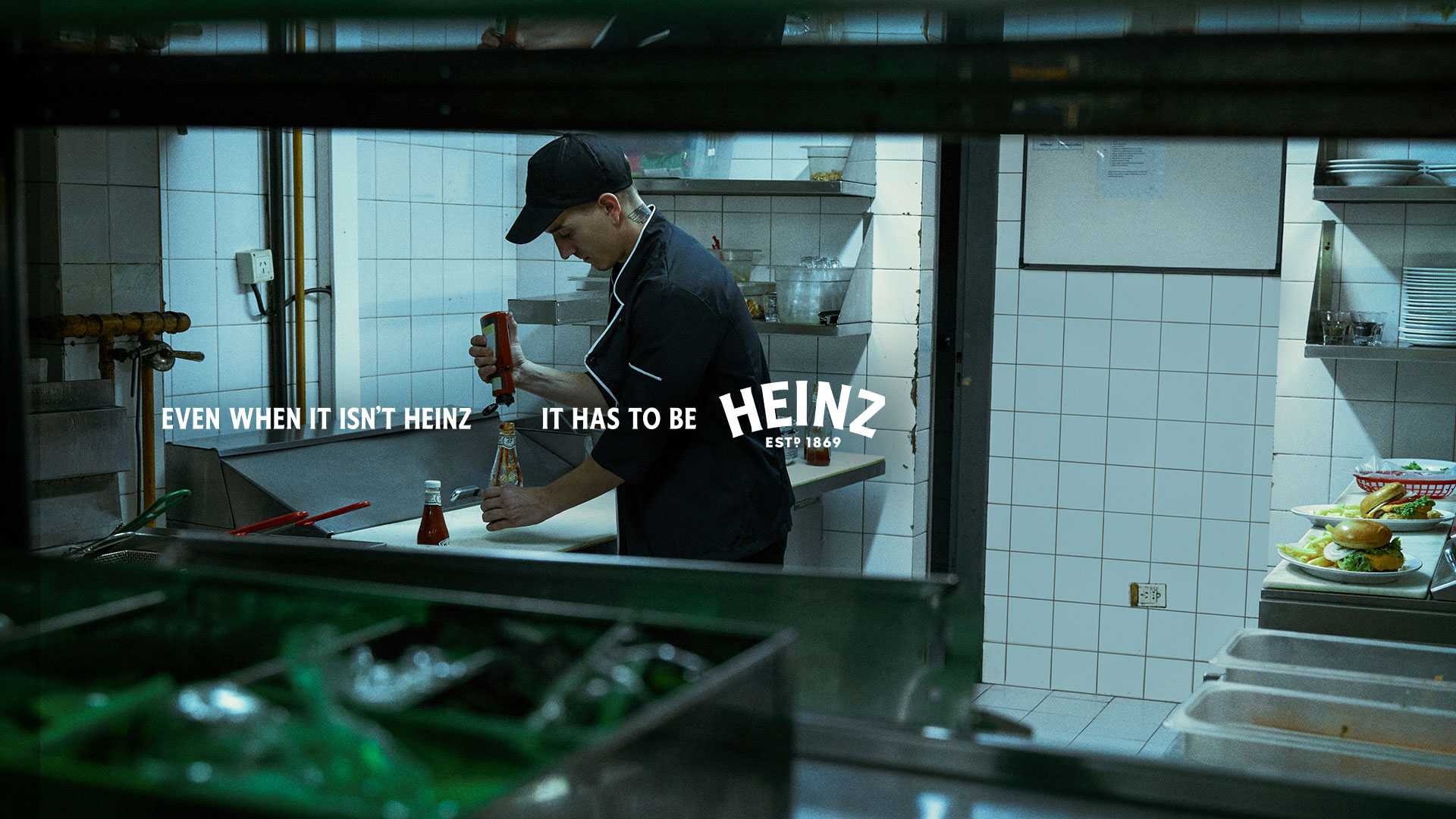

Heinz’s new campaign by the Canadian agency Rethink uses an insight the marketing team gleaned out of a Snapchat post that shows a restaurant employee refilling a Heinz bottle with some other brand of ketchup/tomato sauce.

Using that as a template, Heinz and Rethink came up with 3 print ads and promise to bring the same to outdoor/billboards and social media posts too.

Now, I like the insight and the idea. To extend the insight towards the brand’s famous ‘It has to be Heinz’ is a clever stretch of imagination.

But, on the back of overwhelming praise for the campaign, (see the many, many replies), I do have a couple of observations that go beyond liking it.

Let me start with the insight.

In simple terms, it is the fact that there is a widespread ‘Ketchup Fraud’ (the campaign’s title) going on where restaurants fill a Heinz bottle with other ketchup. There are tons of tweets to back this behavior as being truly widespread (something the press material from Heinz mentions too).

This is a legitimate insight.

The question is: what could/should Heinz do with this insight?

Is this an insight that needs to be directly communicated to the audience? If Heinz did that, as they have done in this campaign, what does it imply to the audience, particularly when you do not see any call-to-action for them at last in the versions of the campaign that Heinz has released so far?

Is it – “Hey folks, that Heinz bottle in your favorite neighborhood restaurant may not be Heinz at all!”?

Or – “You were being served some ketchup inside a Heinz bottle all this while and you had no clue!”?

Or, is it – “Restaurants know that people prefer Heinz. But since not all of them can afford it all the time, they fill some other ketchup inside Heinz bottles. Deal with it!”?

So, Heinz converted a reasonably widespread behavior among restaurants into a campaign targeting end users. So what?

Let me try to answer that myself.

The campaign uses Heinz’s marketing muscle to make this switcheroo more popular than it is now (being mentioned by random people on social media).

All that this campaign does now is,

a. to those who suspected that the bottle of Heinz may not have Heinz after all, they are probably right in their hunch

b. to those who had no clue or don’t care, there is a seed of suspicion

The campaign thought is perfect for the brand’s ‘It has to be Heinz’ positioning. In this case, it is the Heinz bottle alone, not the actual product.

But what does it really do to the brand?

Sure, it asserts the brand appeal undeniably. But, for restaurant folks to refill some non-descript sauce into a Heinz bottle because that’s what customers prefer/seek/want, instead of simply buying Heinz sauce itself, points to a larger problem that Heinz needs to solve before announcing this widespread switcheroo to the end audience.

Heinz should be wondering: why do restaurant owners do this? Is it the cost? (Of course, it is most likely the cost). Availability? What else? If this is widespread enough that so many people point it out on social media, shouldn’t Heinz be trying to figure out the underlying causes behind it and addressing them… and communicate the action taken in a campaign that highlights this switcheroo?

To some extent, that’s precisely what Heinz did in a November 2022 campaign by the agency Mischief. The campaign, called ‘Tip for Heinz‘ asked people to tip an additional $1 when they do not find Heinz at the restaurant, by mentioning next to that tip, ‘Tip for Heinz’ in the bill. When customers take a photo of the bill (with the tip) and send it to Heinz, the brand would reimburse the bill amount (up to $20 per person, till the brand exhausted the $125,000 budget allocated for this campaign). Heinz also offered to provide a free year’s supply of Heinz ketchup to the first ten restaurants that take the ‘tip’ (as a hint) and switched their existing ketchup with Heinz.

In this ‘Tip’ campaign, Heinz had a categorical call-to-action for users when they do not find Heinz, or find some other brand of ketchup.

In the new campaign, Heinz simply seems to be announcing that the switcheroo is widespread without doing anything about it itself, or asking us, the customers, to do something about it to change the situation.

To be fair, Heinz is asking people to tell them where they noticed this switcheroo, at least on Instagram where they are sharing these creatives. But the ask seems very feeble, almost like an afterthought… like, ‘Oh we cracked this great campaign based on actual user behavior, but what’s the point of it to people who see the campaign? Let’s ask them where this happens to spur some engagement at least’. This feeble attempt didn’t really need a fresh campaign – just take a look at the number of people who have mentioned this on their social feed above (there are more!) – all Heinz needed to do was piggyback on some of them and make it a proper user-generated campaign right from the start.

The call-to-action in the ‘Tip for Heinz’ campaign was much more solid and thought-through – the call-to-action was the campaign! But in ‘Ketchup Fraud’, merely stating the truth is the entire campaign idea. But the truth doesn’t do anything for the brand except for fellow marketing folks calling it ‘brave!’. I presume that ‘brave’ sentiment comes from the simple fact that this ad proclaims that restaurants are making do with just the bottle and not buying the actual product being advertised at all!

You could wonder: what should Heinz do when they find a widespread switcheroo happening because restaurants want to save money, but the decision affects the users’ experience? The answer to that would be to incentivize restaurant owners and not necessarily announce (or, before announcing) the switcheroo to the broader public. Why? Because users don’t have a choice in restaurants – they consume what they get. If they don’t like what they get, they are disappointed. Most restaurants don’t allow outside food anyway, so a BYOK – Bring Your Own Ketchup (or BYOS – Bring Your Own Sauce) may not be feasible. That would be like bringing your own bottle of Pepsi into a McDonald’s that serves only Coca-Cola because of a deal between the two companies.

Incidentally, McDonald’s famously parted ways with Heinz in October 2013!

So, what could Heinz do when they find widespread switcheroo happening?

For starters, they could take a cue from a much smaller, lesser-known rival brand of tomato ketchup called Curtice Brothers!

In March 2022, Ogilvy did a hugely inventive campaign for Curtice Brothers using nothing but Tripadvisor reviews as the starting point. Ogilvy scoured through the worst-reviewed restaurants in Berlin, on Tripadvisor, and sent Curtice Brothers’ sauce to those restaurants so that their pathetically reviewed food could possibly be improved. And guess what? The reviews actually improved because the condiment (I shudder to call tomato ketchup/sauce as a ‘condiment’ given the incredibly rich condiments I have grown up with in India, but it is what it is) made even the worst food taste better!

Of course, the base for the Curtice Brothers’ campaign was different – no one knew the brand (unlike Heinz, which the whole world is familiar with and also prefers, at least according to Heinz). So, adding the condiment and showcasing it as a reason for better/improved Tripadvisor reviews was one way to establish the brand name in people’s minds.

In the Heinz ‘Ketchup Fraud’ campaign, restaurants were consciously pulling a switcheroo for whatever reason. Merely announcing and popularizing the switcheroo does wonders for the brand name, no doubt. But it does not seem to address the underlying problem. Or, it doesn’t co-opt the users in helping address the underlying problem the way the ‘Tip for Heinz’ campaign did.

So the simple question is, what should people do if they know/suspect a switcheroo?

Should they call a dedicated number and complain to Heinz? (or the variants – tweet, share on Instagram, tag the restaurant, etc.)

Should they leave a review online with one star less and mention that the one star has been reduced because they suspect a switcheroo (as a way to incentivize the restaurant to avoid the switcheroo)?

Should Heinz gather information about such switcheroo restaurants and do the ‘Intel Inside’ for the top 50 restaurants (‘Heinz Inside’ – both the restaurant and the bottle!)?

Without a follow-up or a call-to-action, what Heinz and Rethink have rolled out so far feels incomplete. It uses a real insight/business truth, but such usage does not seem to have been thought through from the perspective of addressing the problem. Instead, it merely announces that such a problem exists over and above people’s chatter on this already.

And finally, as Joe La Pompe points out in his blog, this idea was first used by BBDO for their client Pepsi, in 2000 when the Sydney Olympics committee banned Pepsi because of a tie-up with Coca-Cola. It seems Pepsi reused the same campaign idea again in 2005.

That reminds me of India’s own ‘Nothing official about it’ campaign by Pepsi by HTA, going up against Coca-Cola which had paid Rs. 10 Crores to become the official sponsor of the 1996 Cricket World Cup! Even though Pepsi wasn’t banned in the tournament venues (as far as I know), it’s possible that the Indian campaign was a precursor of sorts to the BBDO idea, four years later.